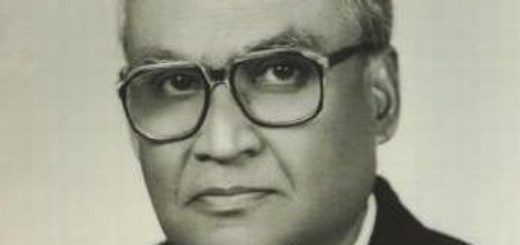

By P.T. Bopanna

Both General K.S. Thimayya, one of India’s most popular generals and India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, were my heroes during my growing up years.

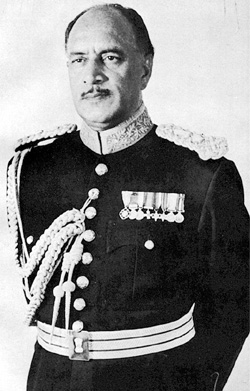

General Thimayya, whose birth anniversary the nation is celebrating on March 31, was a household name in Kodagu (Coorg) from where the general hailed. Madikeri, the district headquarters of Kodagu, was the home town of the general and his statue still towers over the landscape as one enters the town.

Since I also hail from Kodagu, the general was considered a cult hero. Besides winning the 1947-48 Kashmir war for India, General Thimayya was the only Indian officer to be made a brigadier and given command of an operational brigade during the Second World War.

On the other hand, Pandit Nehru was my intellectual hero and I was inspired by his book ‘Discovery of India’ written during his confinement in prison, wherein he reflected on the rich Indian culture. And his book ‘Glimpses of World History’ was about a rambling account of history for young people.

At the dawn of Indian Independence in 1947, both Thimayya and Nehru were towering figures. Nehru was a freedom fighter and Thimayya had made a name for himself as a battle-hardened soldier.

While Thimayya was a pragmatist, Nehru was an idealist, driven by ideology whose economics was mainly shaped by Harold Laski of the London School of Economics.

I feel though Nehru was a patriot, his Soviet Model of economic development was not suitable for India.

Probably, Nehru’s biggest failure was in military affairs because he was suspicious of the Army. This ultimately led to his ‘Himalayan blunder’ and loss of face in India-China war of 1962.

Because of his unfounded suspicion of the Army, Nehru did not trust the men in uniform and started the process of down-sizing the army soon after India attained Independence.

When the first Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Armed Forces, General Sir Robert Lockhart, presented a paper to Nehru detailing a plan for the growth of the Indian Army, Nehru is reported to have countered: “We don’t need a defence plan. Our policy is non-violence. We foresee no military threats. You can scrap the army. The police are good enough to meet our security needs.”

Acting on this concept, Nehru downsized the Army by reducing its strength, especially at a time when the Chinese threat began looming large on the horizon in 1950-51.

During the British rule, the Commander-in-Chief of India was the second most important man in the country after the Viceroy. The Chiefs of the Navy and Air Force were his subordinates.

After Independence, all the service Chiefs, who were still British, were made equal. Nehru separated the Army, Navy, and Air Force from a unified command and abolished the post of the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces.

It was only after the 1947-48 war in Kashmir that Nehru realised the importance of the armed forces.

When India became a Republic in 1950, the President was made the supreme commander of the armed forces, acting through the council of ministers.

Nehru continued to demote the status of the services chiefs in the order of precedence in the official government protocol. This policy has continued over the years to the benefit of politicians and bureaucrats.

Nehru’s apprehension of a military take over in India became acute following a military coup in neighbouring Pakistan after General Ayub Khan overthrew the civilian government in 1958.

General Thimayya, who was appointed the Army chief in 1957, was very popular with the ranks, and was loved by the public. This was apparently not to the liking of Nehru and his Defence Minister Krishna Menon.

General Thimayya had a brilliant military career. The British, as a matter of policy had always avoided giving higher command to Indian officers. General Thimayya was the only Indian officer to be made a brigadier and given command of an operational brigade during the Second World War.

During the 1947-48 Kashmir war with Pakistan, Major-General Thimayya gave an excellent account of himself. He was perhaps the most popular general, loved by men of all ranks in the Army.

It was unfortunate that the cantankerous Krishna Menon was the Defence Minister when General Thimayya took over as the Chief of Army Staff.

The misunderstanding between the Defence Minister and the General came to the fore when General Thimayya sent in his resignation letter to Nehru in August, 1959, following his differences with the Defence Minister over promotions in the Army and the Indian government’s policy of appeasing China.

General Thimayya was fond of the nicer things of life and was often seen enjoying himself in five-star hotels and restaurants in the metropolis of Delhi. When he was Chief Of Army Staff in Delhi, that one morning Prime Minister Nehru sent for him in his office, and obviously tutored by Intelligence Staff, suggested that he should not be seen at public places late at nights as it created a bad impression. To this he humorously replied, ‘Panditji, isn’t that better than planning a coup in the middle of the night?’ Panditji, I believe, laughed it off – such was his confidence in the General’s integrity.”

In fact, General Thimayya had known the Nehru family for over three decades ever since he was posted at Allahabad late in the 1920s and had great respect for them.

The friendship started after Jawaharlal’s father Motilal Nehru invited the General to his home Anand Bhavan, the Nehru family mansion. Among those present on the occasion were Motilal’s two daughters, who would become Mrs Pandit and Mrs Betty Hutheesingh, and several other patriots, including Dr Katju and Tej Bahadur.

General Thimayya who was accompanied by a few Indian officers, told Motilal Nehru that they were Indians first, and that to help the cause of independence they were ready to resign their commissions.

Motilal replied: “Gentlemen, you have my sympathy. But nothing would please the British more than your resignations. For thirty years, we have fought for army Indianisation. We are now winning the fight. If you give up, we shall have lost it.”

Though General Thimayya had good rapport with Nehru family, it was the lurking fear of a coup that made Nehru paranoid.

Both Nehru and Thimayya lived during a turbulent phase in India’s development. Hence it will be not be proper to tar the heroes of India’s freedom movement as the present dispensation is trying to do.

Source: Dateline Coorg by P.T. Bopanna, Rolling Stone Publications, 2010. To know more about the book and also to buy the print or digital edition of the book, follow the link below: